Physical Preparation Activities for Elementary General Music

In music education, the learning phases of preparation, presentation, and practice are unique to the Kodaly framework of teaching and learning. As a part of the preparation phase, teachers lead students through a process of experiencing the target musical pattern without the Western theory musical label or notation.

Physical preparation is a key component of this experience-based learning sequence. Today we’ll explore possible ways to explore rhythmic and melodic elements through the lens of physical preparation activities.

Why Use Preparation?

The preparation process begins with intentional experiences, without using the standard Western notation or the standard Western name for the target musical pattern. This teaching sequence may leave some educators wondering why. Why not just call the sound by the name we’ll use in class later (quarter note, do, etc)? Why not just show the Western notation right at the beginning of the learning process?

Many thoughtful pedagogues do present the name and notation with the sound right away! Presenting the name, sound, and symbol for a melodic or rhythmic concept in the first experience is a valid way of teaching music that can serve students well and develop interdependent inquisitive, and sensitive musicianship.

One of the benefits of walking through the preparation process without the standard Western notation or symbol as the leading vocabulary right away is that it makes room for other descriptions of the sounds.

Students are encouraged to notice and explore the qualities of the sound by engaging in active experiences and making inquiries. Active experiences can include singing songs, speaking rhymes, playing games, playing instruments, moving, collaborating, and creating. Inquiries students might investigate can include questions like Is this pattern long or short? Is it high or low? How much longer or shorter is it compared to other sounds we know? How much higher or lower is it than other sounds we know? Have we heard this pattern in other pieces of repertoire?

In the process of experiencing and inquiring, students use their own language and vocabulary to describe the sounds they hear and make meaning of the patterns. When the teacher shares the common classroom vocabulary, students have already developed the definition.

This process of teaching and learning can be about active experiences, thoughtful descriptions, creative collaboration, and analytic thinking. It is a framework to listen, compare, and apply.

Models of Preparation

One of the beautiful things about any teaching viewpoint is that practitioners who follow it are not monolithic in their embodiment of the approach. While their descriptions of this phase are not opposing, Kodaly thinkers have discussed this phase of learning slightly differently.

Anne Eisen and Lamar Robertson, and Mícheál Houlahan and Philip Tacka group preparation experiences into physical, aural, and visual activities, with physical activities as the first step.

Susan Brumfield groups the process into early, middle, and late preparation. She describes the progression as play (early), recognition, identification, and description (middle), and summarization and representation (late). Brumfield lists aural activities as the first step (p. 13).

Lois Choksy’s work described preparation activities as preparing students “subconsciously through singing and hearing the new rhythmic or melodic turn in a variety of musical settings” (p. 172).

While authors are not uniform in their approach to preparation, the common thread in each of these works is the practice of experiencing a musical element before it is made conscious.

For our purposes today, I’ll consider physical activities to be early experiences in preparation.

Physical, Aural, & Visual Pathways of Musicing

If we were to look at our teaching processes through the lens of Universal Design for Learning, we might decide we want more than one way to represent a musical idea. Physical expression, aural awareness, and visual depiction are three pathways of musicing we explore in preparation.

These learning pathways are sometimes referred to as learning styles or learning modalities. Certainly more than these three styles of learning exist, and students are not locked into one single way of musical knowing. Many educational researchers agree that there is not sufficient research to support learning styles as a significant deterrent or accelerator of learning, at least in the way we have traditionally used them (read studies 1 2 3 4).

In my opinion, the reason to use physical, aural, and visual pathways for preparation has less to do with learning styles. It has more to do with how music exists naturally in the world and how learners take in sensory information.

In my view, music naturally falls into the categories of an action we physically take (to sing, speak, move, or play), a sound we perceive, and a visual representation we can see. These are the sensory experiences we have as we music.

What does music feel like? What does it sound like? What does it look like?

Physical activities are often the first preparation experiences we explore with a new element.

Physical Preparation

We center physical preparation when we emphasize how music feels in our bodies.

From a sensory perspective, what does it feel like for a melody to move down? What does it feel like for a melody to end on the home, tonic pitch? What does it feel like to have a long sound stretched over two beats? What do short sounds feel like?

The use of these experiences will be different depending on the extent to which students are asked to imitate the teacher, and the extent to which they are asked to analyze and embody the information on their own.

For example, students might echo the teacher’s rhythmic clapping patterns using one and two sounds on a beat. After this experience, we could get additional information from students about how they are internalizing one and two sounds by asking them to create a clapping pattern with a partner using the same rhythm.

Both of these experiences utilize a physical action, but they demand different levels of ownership on the part of students.

Which is Which? Combining Physical, Aural, and Visual Ways of Experiencing

Because music is naturally embodied through physical, aural, and visuals modes of expression, very often these categories will blend together.

If the teacher plays a collection of long and short sounds on recorder and asks students to move to what they hear with steps for the long sounds and tiptoes for the short sounds, students will rely on their aural awareness to hear the changes in length. They’ll embody the sounds physically as they tiptoe and step. And they’ll be able to visually see the other student-musicians tiptoe and step as well.

Even though we focus on one specific sensory way of knowing when we engage in physical preparation, all musical interactions naturally involve physical, aural, and visual modes of experiencing music.

Pedagogically, the label we put on an activity will depend on the primary purpose of the event and what we want students to focus on.

Physical Preparation for Rhythmic and Melodic Elements

Rhythmic and melodic elements will be experienced differently when we do physical preparation activities.

When we prepare rhythmic concepts through physical activities, we’ll focus on how the length of the sound feels, especially in relation to the steady beat.

When we prepare melodic concepts through physical activities, we’ll focus on the how high or low the sounds feel in the melodic contour of a phrase.

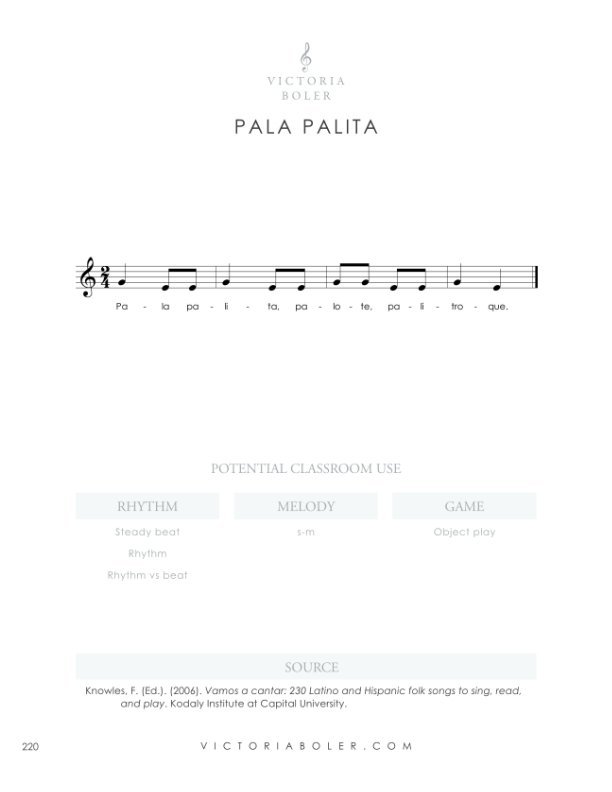

Here are example activities for physical preparation of a rhythmic or melodic element. In each of these examples, students would focus the activity on a specific target phrase of the song, not necessarily the song in its entirety. A target phrase is a phrase or sub-phrase of the song that has the target rhythmic or melodic element, surrounded by other known elements.

Rhythm

Clap the rhythm of the words

Put the rhythm of the words on body percussion (with a partner, with a small group, or individually)

Partners create two different ways to play the rhythmic phrase with body percussion

Play the rhythm on unpitched percussion instruments like hand drums or rhythm sticks

Play the rhythm on pitched percussion instruments

Create a steady beat body percussion pattern (with a partner, with a small group, or individually). Half the class plays their steady beat pattern. Half the class plays their rhythm body percussion

Tiptoe, step, and slide the rhythm of the target phrase in open space around the room

Clap a target word, sing the rest of the song

Melody

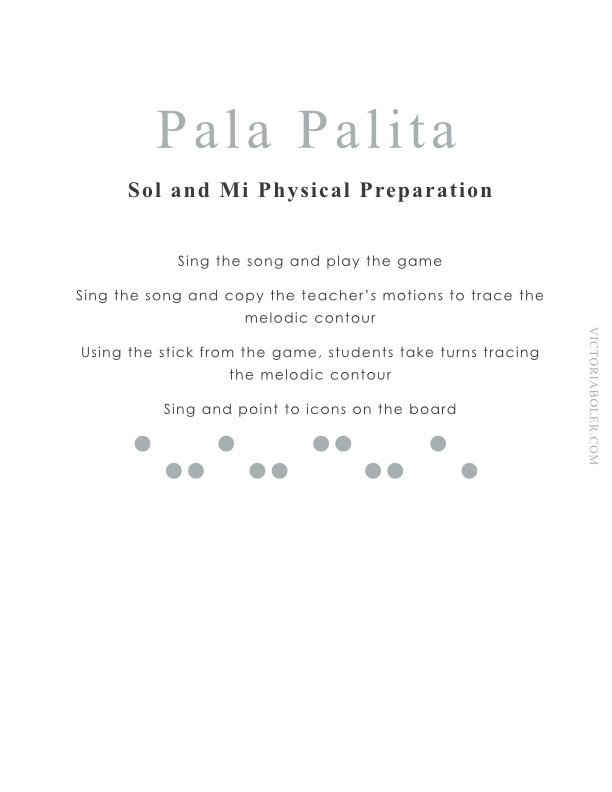

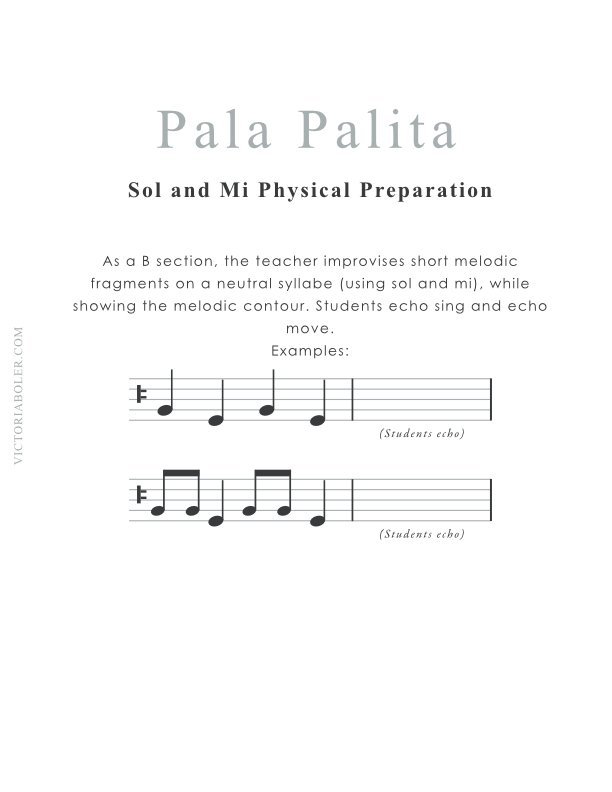

Students copy the teacher’s motions to show melodic contour of the target phrase

Paint the melodic contour with a melodic paintbrush (imaginary paintbrush in the air) and put the paintbrush in several places (nose, elbow, ear, shoe, etc.)

Point to spatial icons to represent the melodic contour (dots on the board, a tone ladder, melodic stairsteps, or a barred instrument)

Point to objects in the room to represent the melodic contour (such as a window and scrap piece of paper on the floor for high and low)

Play the melodic contour with body percussion using high, middle, and low levels

Example: “Frog in the meadow” becomes snap snap snap clap pat

Example: “Come through in a hurry” becomes clap clap pat clap snap

Move to the melodic contour while traveling in open space (individually or with a partner)

Find three different ways to show the melodic contour through movement. Pick your favorite.

Play the melody on a barred instrument

Sing and point to a hand staff, copying the teacher

physical preparation In Action:

What might these examples actually look like?

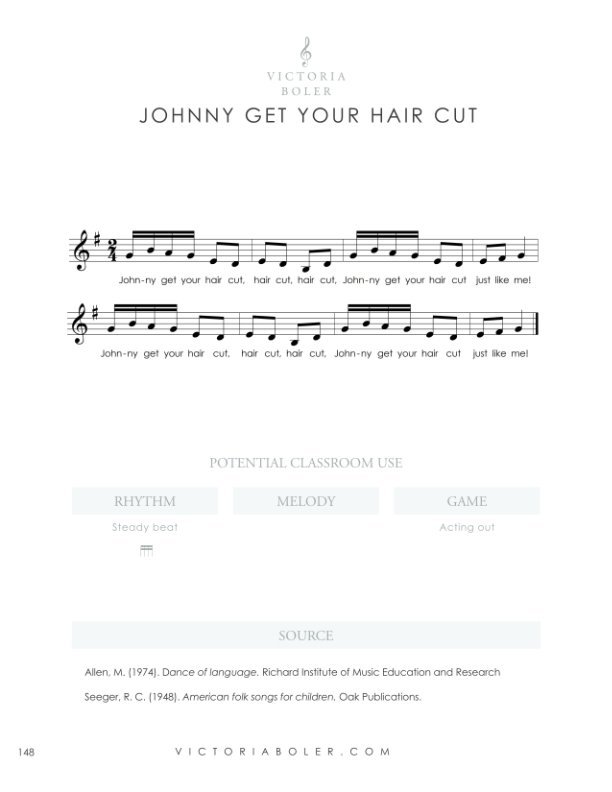

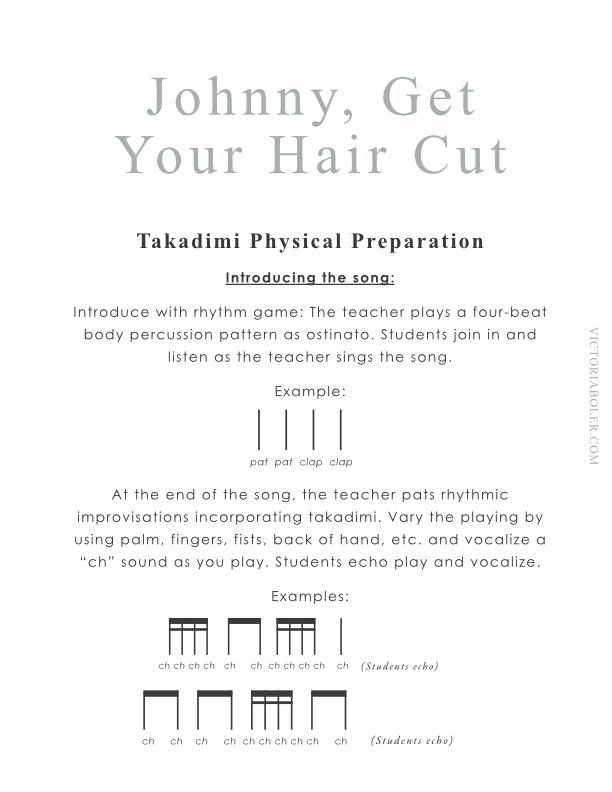

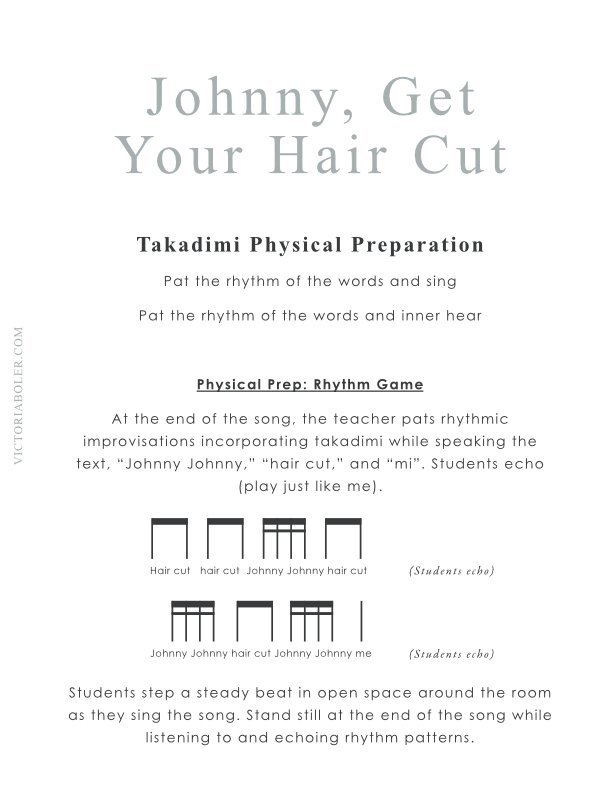

Here are two songs with physical preparation activities to try.

Embodying Music

Today we’ve looked at several ways to facilitate musical preparation from a tactile standpoint.

This emphasis on physical preparation gives learners access to their own bodies as their primary way of musical knowing. It is a uniquely human way of knowing music, with primary experiences happening in human bodies in community - not exclusively through Western notation. Through this learning pathway students explore how music feels and can be experienced.

References & Further Reading:

Brumfield, S. (2014). First, we sing!: Kodály-inspired teaching for the music classroom. Hal Leonard Corporation.

Choksy, L. (2000). The KODÁLY method I: Comprehensive music education. Prentice Hall.

Eisen, A., & Robertson, L. (2010). An American methodology: An inclusive approach to musical literacy. Sneaky Snake Publications.

Houlahan Mícheál, & Tacka, P. (2015). Kodály today: A cognitive approach to elementary music education. Oxford University Press.